Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (NMR) is used to define organic compounds. Carbon (H) and Hydrogen (H) are high in organic molecules. NMR is used for structural analysis because it provides convenience in understanding the molecular structure; this knowledge contributes to scientific development.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (NMR) spectrum interpretation is at the forefront, and it is essential to understand the logic of spectrum measurements and act according to this logic while interpreting. In an atom and its properties, the electrons around the nucleus rotate both around the nucleus and around itself. Still, the movements of protons and neutrons in the nucleus are not noted. That’s why we do not know much about the movement of the nucleus. The nucleus’ protons rotate around their own axis, just as electrons around their own axis. As a result of this movement, the concepts of +1/2 and -1/2 are mentioned. Electromagnetic behaviour due to the spins of protons in the nucleus connects the proton, neutron and their electromagnetic interactions with each other with the logic of being destroyed or not. Like two electrons in an orbital, protons spinning in the opposite direction cancel each other’s electromagnetic effect. So the nucleus does not have a specific magnetic field.

NMR spectroscopy is primarily used by chemists, biochemists, and physicists who are working with complex nanoparticles. Biochemists use it for identifying complex molecules like proteins or intracellular metabolites. It has made a significant contribution to the medical area. Exploratory and diagnostic areas of medicine can exploit the NMR. The medical area is also used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

History of NMR Spectroscopy

The first NMR signal was observed by two separate groups of physicists in 1945. Felix Bloch and Edward Mills Purcell were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952 for their discovery. In the same year, NMR spectroscopy was used in molecular structure determination in chemistry. In 1953, the first NMR devices were produced. After 1970, devices with high discrimination power and sensitivity started to be made. Thanks to his work on developing high-resolution NMR spectroscopy, the scientist named Richard Robert Ernst won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1991.

A chemist/biophysicist named Kurt Wüthrich won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2002, thanks to his method for the investigation of biological macromolecules by NMR spectroscopy. Paul Christian Lauterbur and Sir Peter Mansfield were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2003 for their work in the NMR imaging field.

NMR spectroscopy has been used in chemistry, physics, biochemistry, pharmacy, and medicine to examine the structures of molecules.

NMR Spectroscopy

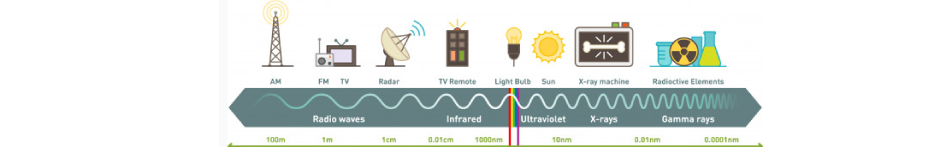

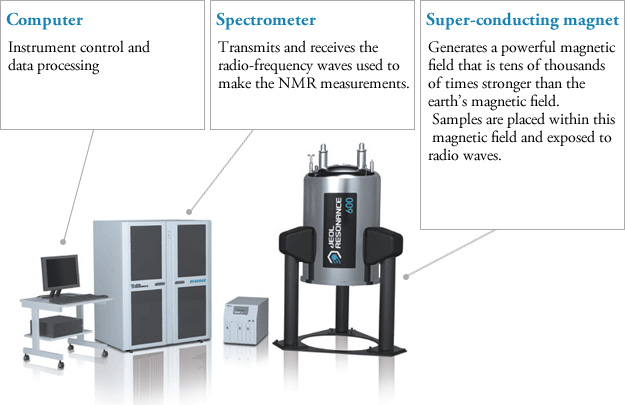

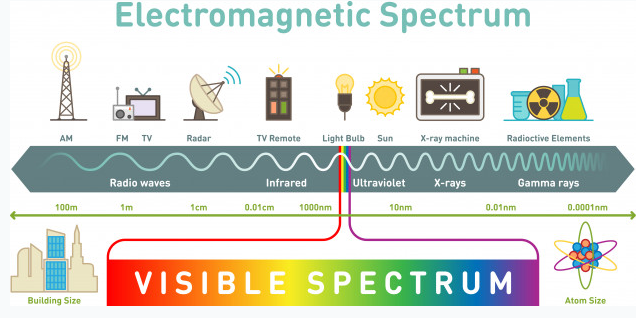

NMR spectroscopy is an illumination method based on the absorption of electromagnetic rays in the radio frequency field by atomic nuclei in a molecule placed in a strong magnetic field. NMR spectroscopy is a technique used in understanding the structure of molecules in the field of chemistry. Hydrogen-containing groups in the molecule and neighbouring groups can also be detected using this method. If evaluated together with the results obtained by other spectroscopic techniques, the structure to be illuminated can be easily reached. In UV and IR spectroscopy, the molecule’s functional groups and the percentages of C, H, O, N, and S atoms in the elemental analysis are determined. NMR spectroscopy gives information about the skeleton of the molecule. Other spectroscopic methods deal with electrons, but NMR spectroscopy deals with the nucleus. NMR requires a strong magnetic field and radio waves, which are long-wavelength rays of the electromagnetic spectrum. NMR spectroscopy does not disrupt the molecule, and analysis samples can be used repeatedly as in UV and IR spectroscopy.

Every atom whose atomic number or mass number is odd has a nuclear spin. The nucleus rotates around itself and is electrically charged creating its magnetic field. Rotating protons behave like bar magnets when placed in an external magnetic field. Rotating protons’ own magnetic fields go either in the same direction with the outer field or in the opposite direction. With the absorption of a photon with a certain amount of energy, the direction of the proton field can change. The energy difference between the two states is directly proportional to the strength of the magnetic field. Protons are surrounded by electrons that protect them from the external magnetic field. Rotating electrons create an exciting magnetic field opposite the external magnetic field and reduce the external field’s influence.

Charged particles rotating around their own axis create electrical and magnetic fields. When these atoms are placed in a stronger magnetic field, two magnetic spins called +1/2 and -1/2 occur. Depending on the direction of the outer magnetic field, the magnetic field due to the atom’s own spin is either added or removed. Thus, the higher and lower energy nucleus can be found.

The small magnetic field in the core and the large applied magnetic field cause the difference in the results of subtraction and addition to be small. This difference changes with the applied external magnetic fields and becomes zero if the magnetic field is not applied. NMR spectroscopy is based on trying to equalise the difference from the external magnetic field with radio frequencies.

Magnetic Properties of the Nucleus and the Basis of NMR Spectroscopy

Some atomic nuclei act like magnets rotating around themselves forming the basis of NMR spectroscopy. Atomic nuclei are positively (+) charged. The nucleus rotates around itself, and the (+) load moves in orbit around the axis, this is the spin motion. Because the nucleus rotates around itself, it also has angular momentum. A dipole and a magnetic field arise from the spin motion. The size of the dipole is called the nuclear magnetic moment (μ), and the angular momentum of the charge is called the spin quantum number (I). To study the NMR of an element, the magnetic moment must be non-zero (μ≠0), and the spin quantum number must be greater than zero (I>0). The spin quantum number varies according to the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus. The spin number can be 0, 1/2, 1, 3/2, 5/2. If I=0, there is no spin. Protons and neutrons have their own spins, and their sum gives the number of spins in the nucleus. Isotopes of an element have different spin quantum numbers.

Proton NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy, like other spectrophotometers, examines samples in dilute media. First, the sample solution to be NMR is taken into a glass tube of 5 mm in diameter and 15 cm in size and placed in a strong magnetic field. Then the radio frequency is sent to the sample. After the sample emits the radio frequency it has absorbed, the detector measures the re-emitted frequency. This change is related to the externally applied magnetic field, and the applied magnetic field must be kept constant throughout the measurement.

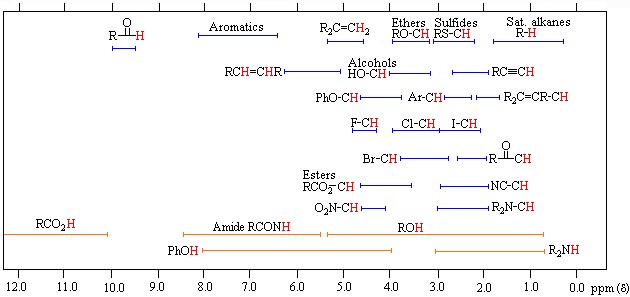

Protons behave differently from each other, which is explained by the electron density around them. Although the proton’s magnetic properties are equal, it is accepted that they will differ in the magnetic environment due to the electron density around it, thus making it easier to understand the spectrum that NMR spectroscopy will give. This difference is minimal compared to the magnetic field and is expressed using ppm (parts per million). Generally, the frequency scale is used instead of magnetic field differences in NMR. The proton resonances of organic molecules are between 0-12 ppm. Highly sensitive devices and systems are required to examine this small range.

The Determination of the Structure of Membrane Proteins using NMR Spectroscopy

Membrane proteins are a part of the biological membranes. They are branched into several types. They can penetrate the cell or be on its surface and have a temporal interaction. Membrane proteins have an important role in the medical area. They are the target structures of the drug. Besides, they have a crucial impact on human and animal diseases. Membrane proteins have the capability of mutating and truncating. While these procedures, several diseases can occur in both humans and animals.

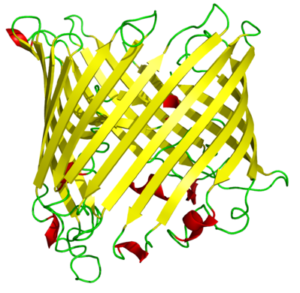

Membrane proteins have a wide range of characteristics, such as being a receptor and interacting with hormones. They can reveal as enzymes and bind to the receptors. Some of them are membrane transporter proteins and impact the transportation of small molecules, macromolecules, and some ions. Their secondary structure is composed mainly of β-barrel, a β-sheet consisting of a first and last strand bonded with hydrogen bonds.

β-barrels mostly can dissolve in water. Strands of the beta barrels contain polar and nonpolar amino acids which lead the protein to have hydrophobic and hydrophilic sides; mostly the hydrophilic part interacts with the solvent because it is a settled surface. The hydrophobic part plays inside of the protein molecule. In proteins containing beta barrels, the hydrophobic side is towards the exterior. They interact with the lipids under the vicinity of it, which surround the protein’s exterior.

GPCRs (G-protein coupled receptors), membrane proteins, are cell signal transportation receptors. The 3D structure of these proteins is determined by NMR spectroscopy. In a region made out of lipids, we can observe how membrane proteins’ motions are reflected. It can be observed in a small area or a large area. As the scientists are supposed to dissolve the substance to mark it on the NMR spectroscopy, they use detergents to dissolve, to denature proteins.

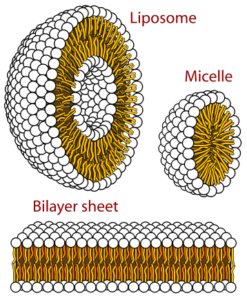

While solubilizing the proteins using detergents, some substances occur—for example, micelles and isotropic bicelles. Micelles are the strewn surface-active molecules’ flocculation. Isotropic bicelles are for the reconstruction of membrane proteins. They patch the proteins with lipid bilayers. Detergents are unnatural substances, so they cause the risk of subverting the protein structure. You can most clearly study the proteins when they are in a phospholipid environment.

The helical membrane proteins can be observed at a high resolution under the bilayers’ favour. They are in an active and immobilised state. On the NMR, substances are well determined in a high-resolution solid state. Bacteriorhodopsin is the first determined helical membrane protein under NMR spectroscopy. It was solubilised with octyl glucoside, which is a type of detergent. Other than NMR spectroscopy, X-rays have also contributed to the determination of membrane proteins. This type of protein was first observed under x-ray diffraction. It was observed during a photosynthetic reaction. The product of this reaction was Rhodopseudomonas viridis (a kind of bacteria), and it was solubilized in a powerful detergent, N, N-dimethyl dodecyl amine N-oxide. The detergent is composed of amphiphilic (both have the characteristic of being hydrophobic and hydrophilic) compounds.

Carbohydrate-Protein Interactions

NMR can identify carbohydrate-protein interactions with the resolution in solvents. This interaction is necessary for the virus-to-cell and cell-to-cell connection. Continuous interaction is provided by the carbohydrate-protein mutual effect for an infection or adhesion event. Even in viruses and pathogens, the outside of the cell is surrounded by glycans. Recognisance and biological transactions are instructed by the mutual effect of the glycans and protein receptors. A variety of molecules can have a mutual effect on carbohydrates. It happens in the vicinity of a mutual effect between L-selectins and glycans terminated by sialic acid.

Influenza infection requires binding to carbohydrates. Hemagglutinin cells (influenza virus) have to be connected to the Siaα-6Gal. The adhesion and growth of tumour cells are supported by β-lactosamine’s mutual effect, which includes galectins and glycans. There are several approaches to NMR. It can be protein-based or ligand-based. A ligand is a complex compound that contains attached biomolecules. If it is protein-based, it will have different solubility characteristics from other solutions. High-resolution attainability requires labelling the protein with C and N stable isotopes. By this labelling procedure, the size will be in the range of 10-25 kDa, which is in NMR standards. There are some protein-detecting methods. In the protein’s 3D structure, the scientist must map the linkage regions of the carbohydrate onto it. The linkage regions are determined by the correlation spectra of H and N atoms. Ligands of carbohydrates must be defined because they are specified from various proteins. In terms of the NMR method (methods of protein detection), it is crucial to compare the proteins in their free state and bound to the carbohydrate state. The labelled protein quantity is dependent on several topics. The first one is the instrumentation of NMR, and the second one is the spectrometer’s available time.

NMR Spectroscopy for the Assignation of Unsaturated Fatty Acids

Fatty acids (FAs) are usually identified by gas chromatography (GC). FAs have to be transformed into methyl esters to assign them to GC. There are saturated and unsaturated FAs. Unsaturated FAs (UFAs) carry one, two or more double bonds and are critical components of animal fats and vegetable oils. UFAs having two or more double bonds are referred to as Polyunsatured FAs (PUFAs). There is a method based on the carbon NMR To determine these bonds’ percentages. Besides, scientists also use hydrogen to quantify UFAs.

Chemical Shift

NMR signals change depending on the magnetic field and radio frequencies. Therefore, radiofrequency change is studied in a standard magnetic field or in a magnetic field change under a standard radio frequency. This problem is avoided by adding a standard substance during NMR measurements. This substance should not affect the hydrogen atom’s electron density with its electronegativity much, and it is tetramethylsilane (TMS) without a solubility problem. All the hydrogens of TMS are equal and at the same point. This point is referenced (point O). The interpretation of where other hydrogen atoms come out according to this point is called the chemical shift. Its unit is ppm, and the symbol represents it. During NMR measurements, it is preferred that the molecules whose spectrum is to be taken be diluted. The presence of hydrogen atoms in the solvent causes the problem of intensity. Some solvents do not contain hydrogen, and generally, not all substances have good solubility. To solve this problem, deutero structures that are not affected by the magnetic field are used. The most common and first tried solvent is deutero chloroform. Solvents such as deutero water, ethyl alcohol, and dimethylsulfoxide are also widely used.

Before making the NMR spectrum interpretation, the electron density around the hydrogen atom must be known from a rough perspective. Compared with TMS, the electron density around a hydrogen atom changes depending on the electronegativity and shielding effect of the atoms to which it is attached. If we accept TMS=0 ppm, Si electronegativity is less than C electronegativity, so the electron density in hydrogen atoms bound to carbon atoms will be less than TMS and shielding less. Thus, we see that radio frequency signals reach the protons in the nucleus and return; thus, excitation and resonance will be easier. It requires less magnetic field, so the ppm gradually increases from 0. Therefore, C-H’s are attached to the carbon atom in molecules that do not contain electronegative, such as 0-1. The chemical shift of hydrogen atoms with low electron density and shielding around them, such as the RCOOH acid proton, is as large as 11–12 ppm. Although there are tables for proton chemical shift values, it is often possible to approximate peaks and locations. It is not always necessary to look at this crowded picture, but it may be necessary with some complex and large molecules.

In the NMR spectrum, the signal intensity depends on the substance concentration. Dilute solutions give weak signals. If the concentration increases, the peak intensity increases. If we take the peaks of different substances at the same concentration, we see that the peak intensity depends on the equivalent hydrogen number. If we take the equivalent concentration of benzene containing 6 equivalents of hydrogen and cyclohexane containing 12 equivalents of hydrogen and measure the NMR spectrum, the NMR spectrum peak intensity of the cyclohexane is twice that of benzene. When these results are combined with the knowledge of how many hydrogen atoms it contains and chemical shift, it makes it easier to understand where the hydrogens of the molecule come out. However, there are still some problems with knowing how many hydrogens each peak equals. However, hydrogen numbers can be calculated from the ratio of peaks to peaks, but instead of exact numbers, they are found in coefficients relative to each other. It is possible to estimate approximate values with this integration method, similar to a simple molecular formula calculation.

In conclusion, NMR spectroscopy has contributed to the determination of various complex molecules like proteins, carbohydrates, enzymes, intracellular metabolites, receptors, and transporters. Understanding these structures by scientists leads to the development of science. Complex molecules are essential to understand various diseases, both in humans and animals. Although NMR is complicated for us, it is a beneficial thing today. That’s why we should try to grasp a complex subject’s logic rather than make it difficult in our minds. The blessings of NMR are countless. It is used in many industries, such as polymer research, synthetic chemistry, petrochemistry, biochemistry, textiles, food, paint, medicine, and agriculture. We can achieve many things using NMR, such as the compound’s nature, structure shape and bonding structure, mixture components, atomic composition, molecular weight and formula, polymer composition and arrangement, and molecular motion. No matter how boring its theory may sound, we do not know how correct it is to call something ‘boring’ that we use somehow.

This article is a part of the home assignment written by Ada Begüm Ögel and Emir Kerem Demiroğlu, two of our 2020-2021 Academic Year Fall Semester Organic Chemistry students.

References

- Alqaheem Y, Alomair AA: Microscopy and Spectroscopy Techniques for Characterization of Polymeric Membranes. Membranes (Basel) 2020; 10.

- Aletli Analiz Yöntemleri: Nükleer Manyetik Rezonans (NMR) Spektroskopisi [http://web.hitit.edu.tr/dersnotlari/gokcemerey_13.10.2015_7A4L.pdf]

- Granger RM, Yochum HM, Granger JN, Sienerth KD: Instrumental Analysis: Revised Edition. Oxford University Press; Revised edition; 2017.

- Nükleer Magnetik Resonans Spektroskopisi (NMR) [http://w3.balikesir.edu.tr/~hnamli/oya/nmr/hnmr.php]

- Staudacher T, Shi F, Pezzagna S, et al.: Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-nanometer)3 sample volume. Science (80- ) 2013; 339:561–563.

- Siegal G, Selenko P: Cells, drugs and NMR. J Magn Reson 2019; 306:202–212.

- Shulman GI, Alger JR, Prichard JW, Shulman RG: Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in diagnostic and investigative medicine. J Clin Invest 1984; 74:1127–1131.

- Bewley CA, Shahzad-ul-Hussan S: Characterizing carbohydrate-protein interactions by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biopolymers 2013; 99:796–806.

- Wider G: Structure determination of biological macromolecules in solution using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biotechniques 2000; 29:1278–82, 1284–90, 1292 passim.

- Campagne S, Gervais V, Milon A: Nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of protein-DNA interactions. J R Soc Interface 2011; 8:1065–1078.

- Simpson MJ, Hatcher PG: Determination of black carbon in natural organic matter by chemical oxidation and solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Org Geochem 2004; 35:923–935.

- Opella SJ, Marassi FM: Structure determination of membrane proteins by NMR spectroscopy. Chem Rev 2004; 104:3587–3606.

- Miyake Y, Yokomizo K, Matsuzaki N: Determination of unsaturated fatty acid composition by high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1998; 75:1091–1094.

- Chalbot M-CG, Kavouras IG: Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy for determining the functional content of organic aerosols: a review. Environ Pollut 2014; 191:232–249.

- Zia K, Siddiqui T, Ali S, Farooq I, Zafar MS, Khurshid Z: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy for Medical and Dental Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Eur J Dent 2019; 13:124–128.